A Case for Standardized Buildings

May 27, 2022

Welcome to a case study exploring the potential of standardized low-rise multifamily development in the City of Los Angeles, California.

Introduction

Take a walk around the Melrose Hill neighborhood of Los Angeles West of the 101 (chances are you don’t live there so Google Street View will suffice). You will likely quickly notice many newly developed low-rise apartment buildings. What you will also see is that these buildings have a lot in common: similar heights and widths, similar numbers of units and fairly similar quality.

All those resemblances are a result of requirements imposed by zoning, overlays, density bonus programs and building codes. In fact, when the requirements of all these regulations are applied (taking financial conditions into account), it becomes apparent that there’s not much design flexibility left to architects and developers.

Yet practically every building there was designed, engineered and developed as bespoke, conducting the entire pre-development process from scratch and carrying over little information between projects. It seems as inefficient, time-consuming, and costly as going to a tailor every time you need to buy new clothes.

We asked ourselves, if the outcome is so similar, wouldn’t it make sense to standardize building design and streamline some parts of the pre-development process?

Precedents

Urban history in the United States and beyond has many examples of standard buildings — both good and bad. Perhaps the most notorious underwhelming examples are social housing projects in the U.S. and panelized housing in Eastern Europe and Asia.

These developments were optimized for cost and density and played an important role in urgently increasing the supply of necessary housing. On the flip side, they contributed to a lasting negative public image of standardized projects and multifamily housing due to poor design, a disregard for the local context, and an unpleasant urban environment.

If done right, standardization is not at odds with beauty or inviting surroundings. Just think of the brownstones in Brooklyn, Haussmann’s boulevards in Paris, etc. In our approach to standardization, we believe that it’s both possible and essential to create beautiful buildings that are respectful of local contexts and traditions.

The level of standardization

Standardization, while having many benefits, always comes at a cost – try to bite off too much and you’ll end up with an overbuilt system that is worse than the bespoke one.

For example, if you’re trying to create the same standards for a building in Los Angeles and one in Chicago, where the local contexts are completely different, you’re almost certainly going to end up with unnecessary elements for either city, if you manage to come up with a working design at all. The same goes for different building typologies within the same city.

We set out to try to find out how much variability there is among Los Angeles land parcels and whether we could create a suite of standard building products for them.

Standard parcels

To create a standard development product, we first needed to locate a critical mass of parcels (or groups of parcels) that share many characteristics. It’s easier said than done, because properties may have different shapes, zoning rules, regulatory overlays, orientation relative to the sun, and location within a block. From the outset, we expected that parcels wouldn’t be entirely identical, but we hoped to discover certain commonalities.

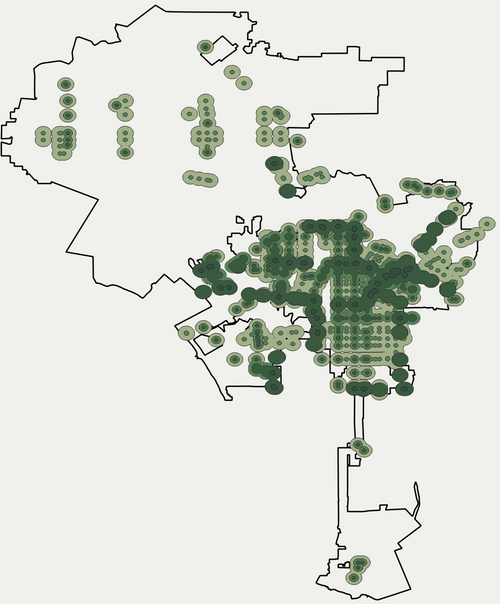

All underutilized lots

In total, we found 23,936 underutilized properties in the City of Los Angeles where new housing could be added according to existing regulations. Those parcels are zoned for 4 residential units or more (multifamily housing) but are currently empty or have only 1 to 2 units on them.

Finding regular parcels

It’s not enough to know that something can be built on these underutilized lots. For standard building products to fit on multiple sites, we need to find parcels that have regular (rectangular or close to rectangular) shapes.

To analyze parcel shapes we defined a spatial metric called Regularity. It compares the area of the parcel shape to the area of its rectangular bounding box. A perfectly rectangular shape would have a Regularity factor equal to 1, because its parcel area is equal to one of its rectangular bounding box. An odd parcel shape (e.g. triangles) would have a smaller Regularity factor, because the difference between its area and the area of its bounding box would be large.

To illustrate how parcels are filtered out at different thresholds of the Regularity factor, let's take a look at an area in the Jefferson Park neighborhood with a concentration of differently shaped parcels.

After analyzing multiple iterations, we set the Regularity to 0.97. Even with such a conservative threshold, we kept close to 87% of all underutilized locations, or 20,799 parcels.

Common dimensions

Now that we had found underutilized parcels of regular (or close to rectangular) shape, we needed to identify the most common width and depth restrictions to inform our standardized building product. We could analyze all the parcels together because the vast majority were in zones with the same setback rules (which would impact building envelopes in similar ways).

We laid out all the unique parcel dimensions on a scatter plot, and we discovered a clear concentration of common characteristics. Specifically, 6,433 parcels had a width of 50 feet and a range of depths between 120 and 150 feet.

Conducting a similar analysis for height restrictions, we found that about 99% of these eligible parcels share a height restriction of 45 feet or less.

Filtering regulations

In theory, an underutilized parcel can be developed by-right according to its zoning. That is, if a project complies with the zoning standards, its approval would be streamlined and not require discretionary review or local community input. In practice, many of the underutilized parcels are located in areas with additional regulatory overlays that introduce complex rules on top of basic zoning requirements. In fact, Los Angeles has one of the highest number of regulatory overlays in the country.

Overlays

Some overlays and conditions can have few to no implications for standardized development (e.g. alcohol sales regulations), while others can have unique requirements that wouldn’t allow a standardized project to be built — environmental restrictions, case-by-case community concerns about the design, historic preservation rules for existing structures, the prescribed use of specific finishing materials, etc.

Such unique and prescriptive overlays and conditions are unlikely to work with the standardized development model. By excluding some of them from our consideration we are left with 8,902 unencumbered parcels. Taking into account the regularly-shaped lots and parcel dimension restrictions, we end up with 3,972 underutilized parcels best suited for a standard building.

Transit Oriented Communities

Not all plan overlays stifle development. Los Angeles is one of the most unaffordable housing markets in the country and the city tried to improve the situation by passing Measure JJJ, also known as the “Transit Oriented Communities (TOC) Incentive Program.” It encourages the construction of affordable housing near heavily used bus and train stations.

If a parcel is located in a TOC zone, development may be eligible for extra housing units, reduced parking requirements, and streamlined approvals. In return, a project must allocate a certain share of units to affordable housing. As the mission of our company is aimed at creating more quality and attainable housing, we eagerly included TOC-eligible parcels in our considerations.

Unfortunately, it will come as no surprise that some communities were not happy with a blanket program increasing density and promoting low-income housing. Neighborhoods like City Center, Central Industrial, Hollywood, North Hollywood, Wilshire Center/Koreatown, and Pacific Corridor — all contested the TOC program. To be on the safe side, we didn’t calculate the bonus program for the eligible parcels in these neighborhoods.

Potential products

For the purposes of this study, we were only interested in low- to mid-rise residential “missing middle” housing. But even within this typology and within one jurisdiction, we were expecting to get more than one standard product. Even if underutilized parcels lots are similar in shape, different zoning may allow for a different number of habitable units to be built on them. For example, two identical lots zoned R3 and RD1.5 would be eligible for a different number of units, requiring two different building products.

To evaluate and prioritize building typologies, we aggregated the total unit potential for each eligible parcel. Ideally, we were looking for a product typology that generated a lot of new units and had a large funnel of potential properties to choose from.

parcel count

(incl. TOC bonus)

From this analysis, the 4-, 6-, and 8-plex typologies were in the lead, both by number of eligible parcels and the habitable units that could be developed on them. Another hidden option would be building a standard 12-unit product on all lots that allow between 12 and 14 units, bringing the total number of units to 8,676. Eventually, standard building products could be developed for all of these typologies.

We chose the 6-plex for our initial focus, primarily because it has a larger funnel of potential properties to target when compared to other products with more units. The 6-plex is also less impacted by vacancies than a 4-plex.

Standard design

We designed a 6-unit townhome-style building specifically for the Los Angeles market. Each unit has both a private entrance and a private roof deck, while the two-bedroom layout makes units suitable and attractive to families, couples, and young professionals alike. The modular layout also created an opportunity to seamlessly extend the building to 7 units for lots deeper than 145 feet.

Key building characteristics

Defining unit mix

To define the unit mix, we took into account market demand, absorption trends, financial performance, affordable housing requirements, and implications for parking minimums. Even though we aspired for the building envelope to be flexible enough to support various unit combinations over time, we had to find a default scenario that would perform well in multiple circumstances.

Ultimately, we settled on an all-two-bedroom layout. It works well for a variety of living arrangements: a couple, a young family, a remote worker with a home office, or even roommates. It performs well financially and has a more reliable absorption than larger units.

Design

When you dream of Los Angeles living, an image that likely comes to mind is that of a single-family house, maybe even in the hills, with a terrace overlooking the city. In approaching the design of our product, we wanted to get close to that desirable experience while maintaining the efficiency of a multifamily building. We came up with a townhome-style arrangement, with each apartment featuring a private entrance and a private rooftop.

Designing a standard building that would be replicated in multiple locations requires a tricky balance. A standard building needs an identity, but not one that would be out of place. It needs to be harmonious, but not blank. The design should be timeless and not trendy (meaning, not minimalist or overly Instagram-friendly).

Standardized development products also don’t necessarily require a similar design for every typology or location. For example, when we conducted a similar study for Philadelphia, PA, we ended up with distinct layouts for duplex buildings of different sizes (small, medium, and large), as well as variable façade treatments.

Prefabrication opportunities

A standard development product can be built in a traditional way, but standardizing development also opens a door to prefabrication. Currently, for a project of that size, prefabrication rarely makes economic sense. Few factories, if any, would take on a project with only 6 units. Even if they did so, their efforts would be unlikely to save time or money.

Standardization changes the calculus, as both developers and suppliers could justify a minimal production volume across multiple identical projects — a scale normally reserved for large, 100+ unit developments.

Prefabricated Wood Framing Panels

5 types

37 panels

CLT Floor Panels

3 types

46 panels

Prefabricated Bathroom Pods

3 types

15 modules

Prefabricated Roof Access Module

1 type

7 modules

We explored partial prefabrication strategies that can be implemented over time. In particular, we engineered provisions for manufactured components, such as bathroom pods, and mass timber floors and structural frame.

Automated underwriting

Now that we have a standard building, can we go and build it on one of these standard parcels? Yes... but private housing development will only happen when the estimated market value of a new project would be greater than the cost of land and construction. How can we determine all of the places where the rents would justify property acquisition for a standard product?

To figure this out, we created a spatial data dashboard that automates financial evaluation of new development across thousands of properties. By fixing a number of important variables like unit mix, as well as soft and hard development costs, we could run the same pro forma on every eligible property and locate the most promising ones.

The dashboard allows for the editing of underwriting assumptions, and it outputs all properties where development meets the desired performance target.

The data assumes cost calculations for 6- and 7-unit buildings according to TOC guidelines, including one rental unit for tenants qualifying as Very Low Income. We benchmarked our project by local submarkets against low-rise buildings which have 4-20 units, were built after 2000, and which are ranked Class A and B. We used multiple proprietary and open source data inputs to generate assumptions (rent, vacancy, cap rates, etc.) on the parcel and neighborhood levels.

The results of this bulk underwriting process are not intended to serve as a final decision-making tool for acquisitions. Think of this as sketching on the backs of a thousand envelopes at once. It helps identify the most relevant properties for off-market outreach and further evaluation.

This tool allows manual inputs and can be used to run sensitivity tests to answer questions such as: what would happen if local rents changed? what properties become available if we remove the regulations filter? and what difference does using union or non-union labor make?

For example, the dashboard vividly illustrates the incredible potential of reducing development costs: a 20% decrease in the construction hard costs leads to doubling the number of sites where development starts to pencil!

Conclusion

We started Apt in pursuit of standardizing housing development to reduce its costs and risks, as well as to increase quality and productivity. The idea was simple: the more repeatable, cheaper, and predictable the development process , the more ground-up projects may pencil, which would create more much-needed housing. Here are some of our main findings:

Standard development is a viable niche

Our research process illustrated that standard building products can be developed on thousands of lots in the City of Los Angeles, making this approach conceptually viable.

However, the conversion funnel shows that only 26% of all underutilized parcels would qualify for standard buildings (8% for the 6-unit building typology). Traditional development still makes sense in the majority of cases where standard products may not fit in, or where they may underperform.

A need for multiple building products and a flexible kit-of-parts

When we conducted a similar study in Philadelphia, PA, we found a far more dispersed distribution of parcel dimensions, likely due to more historic subdivisions. It required us to create not one, but three different designs for the same building category (a small, medium, and large duplex).

A fixed-standard building approach may not be replicable in some markets. Instead, it would require a more flexible parametric software that could apply standard architectural templates to specific site conditions, along with a more flexible building kit of parts. In other words, this approach depends on achieving a healthy balance between the extremes of traditional bespoke construction and rigid standardization.

A new wave of construction startups like Juno, Intelligent City, and Modulous has recognized that too. Such startups are developing parametric architectural software and flexible kits-of-parts allowing for a higher degree of building customization from the outset. We believe in the same future, but we decided to start by focusing on software and standard buildings because it’s a less capital-intensive way to enter the market.

Non-uniform regulations are a major constraint

Various overlays and inconsistent regulations drastically limit the potential of standardized development. In the City of Los Angeles alone, they have removed over half of the otherwise eligible, underutilized parcels from consideration.

The worst part is that the Greater Los Angeles metropolitan area neighboring jurisdictions (West Hollywood, Santa Monica, Culver City, Beverly Hills etc.) all have their own unique zoning and planning regulations, despite having comparable subdivisions, nearly identical demand, and similar climate conditions. Not only does this restrict the potential of standardized buildings, but it complicates housing development altogether.

Parking minimums are a burden on new development

One of the toughest challenges for us, like many other developers and architects we know, is finding a way to accommodate parking minimums and regulations. Even though our 6-unit project benefitted from a reduced parking requirement due to the Transit Oriented Communities program, fitting the required parking lots, and complying with municipal parking codes was a game of inches.

In many instances, parking requirements didn’t allow the building of the full number of units permitted by the density regulations, even in transit-rich areas. In some cases, the required amount of parking physically doesn't fit on a 50-foot-wide site without extremely costly excavation. Parking minimums are a huge and unnecessary burden — not only for standardized development, but for any housing development.

But tides are finally starting to shift in California, and Assembly Bill 2097 eliminating parking minimums for new housing projects within a half mile of public transit has passed the California Assembly on May 26, 2022. If it passes the State Senate it will dramatically increase the opportunities for the development of multifamily housing.

Standardization opens a door for prefabrication

Standardized development is possible with traditional construction methods. It also can help make prefabrication viable by establishing a pipeline of very similar projects.

Prefabrication has not yet gained much traction in the United States because it faces a “chicken-and-egg” problem. Prefab factories need consistent demand from developers to be successful and deliver economies of scale. Developers need immediate cost benefits from prefabrication to justify switching to a new process and a new set of risks.

Initially, the main burden of promoting prefabrication was on startup manufacturers (FactoryOS, Plant Prefab, Katerra, etc); they invested in facilities in the hope that developers eventually would use their standard designs. Ultimately, they had to service bespoke projects and customization requests, negating most of the cost and time benefits of prefabrication.

A new generation of prefab startups like Juno, Madelon, and several others understood the importance of controlling the development pipeline, and they made co-development an essential part of their business model and offering.

At Apt, we design the buildings with prefabrication potential in mind and expect to gradually phase it in.

Standardization can mean better design and sustainability

A standard development product would allow developers to allocate more resources for the architecture and engineering when compared to one-off projects. In contrast to a one-off design, that upfront investment can be recovered across multiple projects while making each of them better designed, more sustainable, and, as a result, more successful. These improvements are especially important for smaller buildings (sub-institutional scale), where thin margins often push developers to skim on architectural costs.

A case for vertical integration

From the beginning, we pursued Natively-Integrated Development — leveraging technology to streamline the development process end-to-end. We envisioned a future where a developer could immediately locate every address eligible for one of the standardized development products, get a thoughtful schematic design of what could be built there while being adapted to the site conditions, and instantly evaluate its financial feasibility.

We started this process by evaluating available software tools and their applicability to standardized development. We discovered that they are primarily suited for traditional development: they target a specific process in the value chain and create a horizontal product that could support extreme customization of one-off projects.

This is not to say that these tools are not helpful, quite the opposite. They established an essential foundation for innovation in the building industry, which has been growing at an accelerated pace.

In order to complete our project, we had to vertically integrate all of these pre-development stages. The required steps ranged from conducting custom GIS analysis; to building proprietary software and data dashboards; to assembling a multidisciplinary team of architects, engineers, land use, code, and prefabrication experts to design fully compliant standard buildings.

This is a complex and costly process and it’s hard to expect developers, especially those working on a sub-institutional scale, to have the resources to develop and maintain similar capabilities in-house. As a result, we are exploring how to share our software and designs with other developers interested in standardizing their development process. In the end, our mission is to support the creation of much-needed beautiful and sustainable housing in cities.

Thank you

We’re grateful for your time and we hope that you discovered something interesting in this case study. We’d love to hear your thoughts, feedback, and ideas for new projects. Feel free to reach us at fed@apt.re.

Credits

compliance consultants

%20C.png)